Animal Worker Occupational Health

Animal research involves a diverse range of hazards, some that pertain to animals, and others are a result of the work being performed. University personnel working in animal care and use environments must receive hazard awareness training, review all pertinent occupational health information, and follow safe and healthy practices.

Zoonotic Disease Information by Species

-

Amphibians

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Amphibians

The overall incidence of transmission of disease-producing agents from amphibians to humans is low. There are, however, a few agents that are found in amphibians and aquarium water that have the potential to be transmitted. In general, humans acquire these diseases through ingestion of infected tissues or aquarium water, or by contamination of lacerated or abraded skin. Exotic amphibians can produce highly dangerous skin secretions, and should be labeled as such and handled with protective gloves. An important feature of many of these organisms is their opportunistic nature. The development of disease in the human host often requires a preexisting state that compromises the immune system. If you have an immune-compromising medical condition, or you are taking medications that impair your immune system (steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, or chemotherapy), you are at risk for contracting diseases and should consult your physician. The following is a list of potential amphibian zoonoses.

Salmonella: This bacterium inhabits the intestinal tract of many animals and humans. Salmonella occurs worldwide and is easily transmitted through ingestion, either direct or indirect. Common symptoms of the illness are acute gastroenteritis with sudden onset of abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and fever. Antibiotic treatment is standard treatment for the illness.

Sparganosis: While unlikely in this area, amphibians can become intermediate hosts to the pseudophyllidean cestode of the genus Spirometra. Disease in man is primarily caused by ingestion of meat or contaminated water. Contact with the muscles of infected frogs is also considered a mode of transmission. Common symptoms include a nodular lesion (bump) that develops slowly and can be found on any part of the body. The main symptom is itching, sometimes accompanied by urticarial rash. Human sparganosis can be prevented by avoiding ingestion of contaminated water and meat, and avoiding direct contact with infected muscles.

Other Diseases: Escherichia coli and Edwardsiella tarda are additional zoonotic organisms that have been documented in amphibians. Human infections are typically acquired through wound contamination or ingestion of contaminated water resulting in gastroenteritis type symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Allergic Reactions to Amphibians: Human sensitivity to amphibian proteins in the laboratory setting is rare. It remains possible, however, to become sensitized to amphibian proteins through inhalation or skin contact. You are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health Director at 951-827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly: If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to animals and their housing materials.

For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation.

For treatment locations:

- Medical Treatment Facilities Guide

- Undergraduate Student Employees report your injury to your supervisor and complete the steps above (or go to Employee Injuries)

- Visiting Faculty, Registered Volunteers and Student Employee Responsibilities: It is important for everyone to notify and communicate with their supervisors prior to going to the doctor or physical therapy appointments and keep their supervisors informed of the status of their injury.

- Undergraduate Students (Non Employee) All students should visit Student Health Services for assistance.

References: http://dels-old.nas.edu/ilar_n/ilarjournal/48_3/pdfs/4803Alworth.pdf

Revised 08/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Amphibians Aeromonas hydrophila Contamination through wounds or various traumas Diarrhea, slight fever, abdominal pains, blood and mucus in feces, weight loss, dehydration, cellulitis Clean and disinfect wounds, personal hygiene, PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Campylobacteriosis Fecal, contaminated food and water Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, visible or occult blood, headache, muscle and joint pain Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Escherichia coli Fecal, contaminated food and water Diarrhea, abdominal pains, fever, vomiting, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, azotemia, thrombosis in terminal arterioles and capillaries Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Klebsiella spps Direct contact, handling Pneumonia, UTI, nosocomial infection, and septicemia Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Mycobacterium ulcerans Handling infected animals Infections start as erythematous nodules on the extremities and gradually become large, indolent ulcers with necrotic base Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Pentastosomiasis Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water Prostatitis, ocular infection, acute abdomen, lacrimation, nasal discharge, dyspnea, dysphagia, vomiting, headaches, photophobia, exophthalmia Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Salmonellosis Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Sparganosis Contaminated food and water Pruritus, urticaria. Ocular sparganosis consist of painful edema of eyelids with lacrimation and pruritus Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Amphibians Burkholderia pseudomallei Contaminated soil and surface water and contact with contaminated wounds Localized skin infection, pulmonary infections and acute blood stream infections Wearing boots in agricultural situations, Universal precautions in hospitals/care facilities and PPE personal hygiene No TBD based on hazard assessment - Medical Treatment Facilities Guide

-

Bats

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Bats

Bats in Southern California keep insect populations in check and are pollinators and seed spreaders, and all these are essential ecosystem roles. However, bats also carry diseases dangerous to public health, which is why it’s so important to ensure their removal if you find evidence of these wild animals in your home.

Transmission of Zoonotic Diseases

Transmission of zoonotic diseases from animals is primarily by direct contact, fecal-oral contact, indirect contact with invertebrate vectors and contaminated inanimate objects, or inhalation of aerosolized materials. Transmission of zoonotic diseases can be prevented through a variety of means, including use of protective clothing, prevention of bites and scratches, proper sharps handling procedures, medical surveillance and vaccination programs, and post-injury treatment.

- Handle animals appropriately and safely, (wear appropriate protective equipment) to prevent bites and scratches.

- Thoroughly wash any bite or scratch wounds and report injuries. Rabies exposure is reportable to public health authorities.

- Do not eat, drink, apply makeup or use tobacco products while handling animals or in animal housing areas.

- Wear gloves when handling animals, animal tissues, body fluids, and waste and wash hands after contact.

- Wear dedicated protective clothing such as a lab coat or coveralls when handling animals. Launder the soiled clothing separate from your personal clothes and preferably at the animal facility.

- Wear respiratory protection when appropriate.

- Keep animal areas clean and disinfect equipment after using it on animals or in animal areas. Do not use cleaning techniques such as vacuuming or power washing which aerosolize animal waste and allows for inhalation of possible pathogens.

Most importantly, familiarize yourself with the animals that you will be working with and the potential zoonotic diseases associated with each species. If at any time, you suspect that you have acquired a zoonotic disease, inform your supervisor and seek medical care.

Why Bats Carry Diseases

California’s several species of bats are natural carriers or vectors of infectious disease. This is mainly due to the way bat populations live. In their roosts, bats snuggle together for warmth. This creates many opportunities for viruses and bacteria to spread between them. The roost is also the place where bats urinate and defecate. If disturbed and inhaled, bat guano can harm humans.

Most viruses cannot survive temperatures above 104 degrees F, which is the approximate internal temperature of a bat during flight. Therefore, many of the diseases that are passed from one individual to another in the roost are killed before they make the bat ill.

However, those viruses and bacteria that are able to tolerate these temperatures remain and are the ones that are of concern to human health.

Potential Zoonotic Diseases

Pathogen/Hazard Route of Tranmission Clinical Symptoms (in humans) Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance / at UCR Rabies (and other lyssaviruses) Bite or scratch from an infected bat; saliva contact with broken skin or mucous membranes. Fever, headache, weakness, progressing to confusion, paralysis, coma, and death if untreated. Rabies vaccination; PPE; avoid direct contact; immediate wound cleaning & post-exposure prophylaxis. Yes, UCR will provide vaccines for rabies as part of the Occupational Health Program and any medical clearance needed. Ensure documented vaccination or declination; immediate report of bites/scratches. Histoplasmosis Inhalation of spores from guano or droppings. Fever, cough, chest pain, fatigue. Respiratory protection (N95); restrict access; good ventilation; housekeeping. Medical evaluation if symptomatic after exposure. Salmonellosis Fecal-oral (contact with droppings, contaminated surfaces). Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal cramps. Handwashing, gloves, surface disinfection, no eating/drinking in work area. Standard surveillance. Leptospirosis Contact with urine or contaminated water/soil. Flu-like symptoms; can progress to kidney/liver failure. Avoid direct contact; PPE; good housekeeping. Evaluate if exposure suspected. Emerging viruses (e.g., henipaviruses, coronaviruses) Contact with bat tissues, guano, or intermediate hosts. Respiratory illness or systemic infection. Risk assessment; containment protocols; PPE; and IBC review. Based on pathogen and risk level. The Occupational Health Program is designed to inform individuals who work with animals about potential zoonoses (diseases of animals transmissible to humans), personal hygiene and other potential hazards associated with animal exposure.

Bats carry several diseases that are zoonotic or directly transmissible to humans without an intermediate host.

Rabies

There is a longstanding belief that all bats carry rabies. It’s true that a small percentage of bats do carry the disease. As well, the chances of contracting rabies is very low, simply because bats don’t typically attack humans. However, an infected bat living in an attic can enter a bedroom and bite a human. A bat may not appear ill, but may bite a human or pet who tries to capture it.

Whether or not a bat appears ill, any bat bite to a human or pet should receive immediate medical attention. A rabies vaccine must be given before symptoms appear to avoid high fatality risk.

Salmonella

Close contact with bats can cause the transmission of salmonella bacteria. The diarrhea, fever, headache, vomiting, and abdominal pain associated with this bacteria can usually be treated with fluids and rest. In some cases, medically administered hydration may be necessary.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a fungus that can be transmitted by Southern California bats to humans. Affecting the respiratory system, histoplasmosis is found in bat guano and, when disturbed, releases spores that can be easily inhaled unless a person is wearing protective equipment.

Once infected, a person can experience flu-like symptoms at the outset. If left untreated, histoplasmosis can affect hearing, vision, and the heart. In its later stages, the fungus can cause fever, blood abnormalities, pneumonia, and death.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a bacteria that lives in the urine of infected bats and other animals in the United States. Although rare, this bacteria can be fatal if contracted by a human. As well, while bats are not the main carriers of leptospirosis, handling bats or their waste without hand or eye protection can cause transmission of the bacteria to humans through mucous membranes and broken skin.

Left untreated, leptospirosis is rarely fatal. However, it can cause complications in some people. Muscle pain, headaches, and fever, along with nausea and vomiting, are all symptoms of leptospirosis, which can be treated with antibiotics.

Emerging Viruses (Henipaviruses, Coronaviruses, and Others)

Bats are recognized as reservoirs for several families of emerging viruses with significant zoonotic potential, including henipaviruses (Hendra and Nipah), coronaviruses (such as SARS-related and MERS-related strains), and filoviruses. These viruses can cause severe respiratory or neurologic illness in humans, with high case fatality rates in some instances. Transmission may occur through direct contact with infected bats, their secretions (saliva, urine, feces), or indirectly via intermediate hosts such as livestock or wildlife. While no known spillover of these agents has occurred at UCR or within managed colonies, the potential risk underscores the importance of rigorous biosafety practices, adherence to BSL-2 or higher containment for relevant procedures, use of appropriate PPE, and institutional oversight through IBC and Occupational Health. Personnel working in field or laboratory settings must be trained to recognize exposure risks, maintain good hygiene, and promptly report any suspected contact or illness following bat handling.

Risk Assessment and Oversight

- Conduct a hazard assessment for all bat-related work: species, source, housing/field conditions, tasks (handling, sampling, necropsy, guano removal), PPE, and training.

- Oversight by IACUC, IBC, and Occupational Health (OHSS).

- Supervisors ensure personnel are trained and competent in SOPs, PPE, exposure response, and waste disposal.

Field Capture and Handling of Wild BatsBefore conducting any fieldwork involving bats, personnel must complete a pre-field risk assessment to evaluate terrain conditions, wildlife interactions, and emergency response procedures. Respirator fit testing should be performed for anyone required to wear respiratory protection due to potential airborne exposure risks. After field activities, all equipment, clothing, and sampling tools must be thoroughly decontaminated to prevent cross-contamination between sites or introduction of pathogens into other environments. Workers should continue to monitor their health for any signs of illness following field exposure and promptly report symptoms to Occupational Health for evaluation.

When capturing or handling bats in the wild, personnel must wear appropriate protective equipment to prevent bites, scratches, and exposure to zoonotic agents. At minimum, workers should wear thick leather or bite-resistant gloves, long-sleeved shirts, and pants made from durable materials to minimize skin exposure. An N95 or higher-rated respirator should be worn when working in areas with accumulated guano or where aerosolized particles may be present. Eye protection or a face shield is recommended to protect mucous membranes from splashes or debris, particularly during close handling or sampling. A hat or head covering and sturdy boots are advisable in roosting or cave environments to protect from falling debris and contact with contaminated surfaces. Rabies pre-exposure vaccination is mandatory for anyone engaged in field bat work, and personnel should carry a first aid kit for immediate wound cleaning and have an emergency plan for reporting and managing bites or scratches.

Safe Work Practices & Controls

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE):

- Waterproof gloves, eye/face protection, N95 respirator (if disturbing droppings), long-sleeved protective clothing, and boots.

- Rabies pre-exposure vaccination for high-risk workers.

Hygiene & General Practices:

- No eating, drinking, smoking, or cosmetics in bat work areas.

- Wash hands after handling bats/materials.

- Decontaminate gloves/tools/surfaces.

- Prompt wound cleansing and incident reporting.

- Restricted access to work areas with appropriate signage.

Medical Surveillance

All personnel who may handle or be exposed to bats must either maintain up-to-date records of their rabies vaccination or formally document a declination of the vaccine. A pre-placement medical evaluation is required for anyone designated as a bat handler. Additionally, individuals who are immunocompromised or who work with wild bats must be closely monitored and included in health surveillance protocols that align with UCR’s occupational health rabies program (link opens in a new tab).

Training

All personnel working with bats must receive comprehensive training covering zoonotic disease risks, proper bat handling techniques, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), incident response procedures, and waste management protocols. Those conducting fieldwork must also be trained in first aid, identification of remote-site hazards, and safe wildlife handling practices. Documentation verifying completion of all required training must be maintained.

Animal Handling & Housing

Animal handling and housing practices should include quarantining all new animals and maintaining accurate veterinary records. Housing must be escape-proof and equipped with proper ventilation and environmental controls to ensure animal welfare and safety. When capturing animals in the field, personnel should follow established field safety protocols, wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), and be prepared to administer first aid if necessary. Additionally, guano should always be treated as potentially infectious material, handled carefully, and cleaned using wet methods and approved disinfectants.

Waste and Decontamination

Bat tissue, carcasses, and guano should always be treated as potentially infectious waste. Decontamination procedures must include the use of bleach or other approved disinfectants to ensure proper sanitation. All samples must be clearly labeled and transported in accordance with established biosafety and shipping regulations.

Exposure/Incident Response

In the event of an exposure or incident, any bites or scratches should be immediately washed with soap and water, followed by notifying the supervisor and contacting Occupational Health. If exposure occurs through mucous membranes or aerosols, the affected area should be flushed thoroughly, and the incident should be reported right away. All incident report forms must be completed, and a medical evaluation should be sought promptly if rabies exposure is suspected to determine the need for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). Any post-exposure symptoms that develop should also be reported without delay. Please contact the Occupational Health at 951-827-5528.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly. If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to animals and their housing materials. For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation (link opens in a new tab). For treatment locations visit: Medical Treatment Facilities (link opens in a new tab).

References

Cornell University Environmental Health and Safety. (n.d.). Bat zoonoses guidance. Cornell University.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Rabies prevention and exposure management. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Letko, M., Seifert, S. N., Olival, K. J., Plowright, R. K., & Munster, V. J. (2020). Bat-borne virus diversity, spillover and emergence. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 18(8), 461–471.

Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. (n.d.). Zoonoses – bats.

Bat Conservation Trust. (n.d.). Bats and disease guidance.

-

Birds

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Birds

Birds can carry organisms that may be potentially infectious to humans. Bird colonies in the laboratory setting are normally closely managed to produce high quality, healthy animal models. The likelihood of a person contracting a disease from a bird is very low. However, there is always a risk of an outbreak occurring within a colony, either from a new bird being introduced into an established colony or from individuals inadvertently contaminating a colony by wearing shoes or clothing that have been in contact with asymptomatic disease-carrying birds. A disease, such as psittacosis, is infectious both to other birds and to people. Therefore, an outbreak within a colony could significantly increase the risk of human exposure.

Psittacosis (Ornithosis, Chlamydiosis): Psittacosis is a disease caused by the bacteria, Chlamydia psittaci. Psittacosis is common in wild birds of all types and can occur in laboratory bird colonies as well. The reservoir/source of infection to people is infected birds, especially ones displaying symptoms (diarrhea, respiratory signs, conjunctivitis and nasal discharge.) This disease is highly contagious to other birds as well as humans. Transmission may be through direct contact or from aerosolization with exudative materials (e.g. pus), secretions or feces. Direct contact with the bird is not necessary. In people, the disease occurs 7-14 days after exposure. An infected human may develop a respiratory illness of varying severity, from flu-like symptoms in mild cases to pneumonia in more significant infections. Serious cases can result in extensive interstitial pneumonia and rarely hepatitis, myocarditis, thrombophlebitis, and encephalitis. It is responsive to antibiotic therapy. Relapses occur in untreated infections.

Salmonellosis: Salmonellosis is a disease caused by the bacteria species Salmonella. It is one of the most common zoonotic diseases in humans. Birds and reptiles (especially iguanas) are the animals most frequently associated with Salmonella. Most people typically contract the disease by consuming food or water contaminated with the bacteria. Symptoms include diarrhea (usually watery, and occasionally bloody), nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, and abdominal cramps. If the bacteria leaves the blood stream and enters the central nervous system, meningitis/encephalitis may develop. Salmonellosis is a very serious disease in humans, especially for young children and people with compromised immune systems.

Newcastle disease and Avian Tuberculosis: Newcastle disease is a serious and fatal viral disease in avian species. Affected birds may demonstrate neurological signs that progress to death. Definitive diagnosis is through viral isolation of the organism. The disease is quite contagious among birds and has zoonotic potential that often may go unrecognized. Clinical signs in people most commonly involve a mild conjunctivitis, which is self-limiting. Mycobacterium avian (and possibly other species) is a causative agent of tuberculosis. Affected birds may carry the disease for years, and intermittently shed organisms. Humans are more commonly infected with M. tuberculosis and occasionally M. bovis. It is believed that immunocompetent humans are resistant to the strains of tuberculosis found in birds, but immunocompromised people, such as those infected with HIV, those on chemotherapy, the elderly and children, are at increased risk. In adults, tuberculosis frequently affects the lungs, producing respiratory signs. People who are infected with human tuberculosis should not own birds since they can serve as a source of infection for their pets.

Allergic Reaction to Birds: Various bird proteins have been identified as sources of antigens involved in both allergic reactions and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a lung condition with symptoms that mimic pneumonia. Symptoms develop after repeated exposure to a specific antigen. Signs of an allergic reaction after exposure to birds are rhinitis and asthma symptoms (wheezing and dry cough). Signs and symptoms of both allergic reactions and hypersensitivity pneumonitis usually occur several hours after exposure. To reduce exposure, perform procedures in a laminar flow hood whenever possible. If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health Director at 951-827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

How to Protect Yourself

Wash your hands. The single most effective preventative measure that can be taken is thorough, regular hand washing. Wash hands and arms after handling birds, their cages and their water. Never smoke, drink, or eat in the animal rooms or before washing your hands.

Wear Personal Protective equipment. If you handle birds select the appropriate gloves for the job, and when in close contact with birds of unknown origin wear respiratory protection. For more information please contact the Occupational Health Director at 951-827-5528 or visit the website for more information.

Tell your physician you work with birds. Whenever you are ill, even if you're not certain that the illness is work-related, always mention to your physician that you work with birds. Many zoonotic diseases have flu-like symptoms and would not normally be suspected. Your physician needs this information to make an accurate diagnosis. Questions regarding personal human health should be answered by your physician.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly. If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to birds. For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation.For treatment locations:

- Medical Treatment Facilities Guide

- Undergraduate Student Employees report your injury to your supervisor and complete the steps above (or go to Employee Injuries)

- Visiting Faculty, Registered Volunteers and Student Employee Responsibilities: It is important for everyone to notify and communicate with their supervisors prior to going to the doctor or physical therapy appointments and keep their supervisors informed of the status of their injury.

- Undergraduate Students (Non Employee) All students should visit Student Health Services for assistance.

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Birds Campylobacteriosis Fecal/Oral from contaminated food and water Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, visible or occult blood, headache, muscle and joint pain Personal hygiene or PPE No TBD based on hazard assessment Birds Newcastle disease virus Contact with animal, inhalation of aerosols Congestion, lacrimation, pain, swelling of subconjunctival tissues, slightly elevated temperatures, chills, pharyngitis Personal hygiene, use of respirator No TBD based on hazard assessment Birds Psittacosis Airborne or direct contact Respiratory symptoms Screening of bird flocks. Very transmissible, use PPE, personal hygiene No TBD based on hazard assessment Birds Salmonellosis Fecal/Oral, contaminated food and water Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever Personal hygiene No TBD based on hazard assessment Revised 08/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

- Medical Treatment Facilities Guide

-

Cats

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Cats

Cats are generally social animals and respond well to frequent, gentle human contact, however, any cat can become agitated when being restrained for procedures. Due to the penetrating nature of their bites, cats can inflict serious bite wounds and prompt first-aid is particularly important when dealing with such injuries. Cat bites should be reported to the supervisor and EH&S via the online incident form (link opens in a new window). Scratches are also a hazard when dealing with cats. It is essential that training be provided to all employees who handle cats in order to avoid injury. The following is a list of potential zoonotic diseases associated with cats.

Cat Scratch Disease: Caused by bite, scratch, or lick of a cat. Casual agent of the disease is not clearly defined. The disease is benign and heals spontaneously (from 7 to 20) days after symptoms appear and is characterized by regional lymphadenopathy (swollen glands) along with signs of a mild systemic infection consisting of fever, chills, generalized pain, and malaise.

Toxoplasmosis: A protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii has its complete life cycle only in cats, which are the only source of infective oocysts. Other mammals (including people) may become intermediate hosts. It takes at least 24 hours for oocysts shed in the feces to become infective, so removal of fresh feces daily reduces the risk of acquiring infection. Toxoplasmosis in people resembles mild flu-like symptoms unless immune suppressed (in some individuals it may cause ocular and neurological disease). Infection in a previously uninfected pregnant woman can result in prenatal infection of the developing fetus, which can cause birth defects. Should an accidental mucosal or needle stick exposure occur, medical services should be obtained through Workers Compensation (link opens in a new tab). For treatment locations visit: Medical Treatment Facilities (link opens in a new tab).

Ringworm: Dermatophyte infection (most commonly Microsporum spp. and Trichophyton spp.) is commonly known as ringworm because of the characteristic circular lesion often associated with it. Dermatophytes are classified as fungi and may not be readily apparent. Disease in people is from direct contact with an infected animal. Ringworm is usually self-limiting and appears as circular, reddened, rough skin. It is responsible to prescription topical therapy.

Pasteurella multocida: This bacterium resides in the oral cavity or upper respiratory tracts of cats. Human infection is generally associated with a bite or scratch. Human infection generally appears as local inflammation around the bite or scratch, possibly leading to abscess formation with systemic symptoms.

Rabies: Rabies virus (rhabdovirus) can infect almost any mammal. The source of infection to people is an infected animal. The virus is shed in saliva 1-14 days before clinical symptoms develop. Any random-source (animal with an unknown clinical history) or wild animal exhibiting central nervous system signs that are progressive should be considered suspect for rabies. Transmission is through direct contact with saliva, mucus membranes, or blood, e.g. bite, or saliva on an open wound. The incubation period is from 2 to 8 weeks, possibly longer. Symptoms are pain at the site of the bite followed by numbness. The skin becomes quite sensitive to temperature changes and laryngeal spasms are present. Muscle spasms, extreme excitability, and convulsions occur. Rabies in unvaccinated people is almost invariably fatal. Rabies vaccine is available through Occupational Health Services for laboratory workers who may be repeatedly exposed to the rabies virus. Please contact the Occupational Health at (951) 827-5528.

Other Diseases: There are several other diseases that can be possibly spread through working with cats. Cryptosporidia, Giardia, and Campylobacter are transmitted via the fecal/oral route. These diseases in people are exhibited by acute gastrointestinal illness; diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and fever. Clinical signs are generally brief and self-limiting.

Allergic Reactions to Cats: Allergies to cat fur and dander are well documented. The major allergen in a cat is a protein that is produced in the sebaceous glands of the skin, which coats the hair shafts. This protein is also found in the saliva of cats. If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact Occupational Health at (951) 827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Tell your physician you work with cats. Whenever you are ill, even if you are not certain that the illness is work-related, always mention to your physician that you work with cats. Many zoonotic diseases have flu-like symptoms and would not normally be suspected. Your physician needs this information to make an accurate diagnosis. Questions regarding personal human health should be answered by your physician.

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Reference Cats Afipia felis Scratch, bite or licking. Localized lymph glad swelling, fever, chills, anorexia, malaise, generalized pain vomiting, stomach cramps. Avoid cat scratches and bites, cut cat's nails, wash and disinfect any scratch or bite, wash hands after petting or handling a cat. No TBD J Clin Microbiol. 1998 Sep;36(9):249 9-502 Cats Bartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae- Cat Scratch Fever Fleas, bite, scratch. Fever, weight loss, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, lymphadenopathy, muscle and joint pains, headache, meningism, photophobia. Control cat fleas, treat infected cats with antibiotics, any wound inflicted by cat should be promptly washed with soap/water. Seek medical care for all bites. No TBD PAHO zoonoses Cats Bergeyellla (Weeksella) zoohelcum Bite. Cellulitis PPE. No TBD J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Jan;42(1):290-3. Cats Brucella suis Contact with animals and newborn animals, ingestion of animal products, inhalation of airbone agents, contaminated food and water. Fever, chills, profuse sweating, weakness, insomnia, sexual impotence, constipation, anorexia, headache, arthralgia, general malaise, irritation, nervousness, depression. Personal hygiene, use of protective clothes, and disinfectants. No TBD PAHO zoonosess 42-43; also negative PubMed central Cats Campylobacteriosis Fecal, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, visible or occult blood, headache, muscle and joint pain. Personal hygiene, PPE. No TBD Cats Capnocytophaga canimorsus Bite. Meningitis, endocarditis, septic arthritis, gangrene, disseminated intravascular coagulation, keratitis. Irrigation with water, clean with soap and water. Medically treat all bites. No TBD Cats Chlamydia psittaci (feline strain) Inhalation of airborne agent; humans and wild animals contract infection through birds. Fever, chills, sweating, myalgia, loss of appetite, headaches, weakness, coughing, enlargement of liver and spleen, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, insomnia, disorientation, mental depression, delirium Use of PPE. No TBD Cats Cowpox Scratch, bite. Lesions occur on hands, sometimes face and arms. Fever, local edema, lymphadenitis. Avoid contact with sick animal, vaccinia MVA strain. No TBD Cats Cutaneous larva migrans Contact with contaminated soil. Intense pruritis, lesions to skin exposed to contaminated soil. Regular treatment of animal, removal of feces twice a week reduces contamination. Areas susceptible to contamination should be kept dry, clean, and free of vegetation. No TBD Cats Dermatophytosis Contact with animal, spores contained in the hair dermal scales. Acute inflammatory lesions. Avoid contact with sick animal, isolate animal and treat with topical antimycotics or griseofulvin administered orally. Remains of hairs and scales should be burned and rooms, stables, and all utensils should be disinfected. No TBD Cats Dipylidium caninum Ingestion of flea. Diarrhea, colic, irritability, erratic appetite, insomnia. Eliminate fleas and cestodes from animal. No TBD Cats Leptospirosis Skin abrasions and the nasal, oral, and conjunctival mucosa, contaminated water and foods. Fever, headache, myalgias, conjunctivitis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, prostration, petechiae on the skin, hemorrhages in the gastrointestinal tract, proteinuria, hepatomegaly and jaundice, renal insufficiency with marked oliguria or anuria, azotemia, electrolyte imbalance, stiffness of neck. Personal hygiene, use of protective clothes. No TBD Cats Pasteurella multocida Scratch, bite, Diseases of respiratory system, localized infections in different organs and tissues. Measures to reduce likelihood of bites. Medical treatment for all bites. No TBD Cats Plague Flea bite, skin abrasions or bites, Fever, chills, cephalalgia, nausea, generalized pain, diarrhea, constipation, toxemia, shock, arterial hypotension, rapid pulse, anxiety, staggering gait, slurred speech, mental confusion, prostration. Flea and rodent control, inactivated vaccine. No TBD Cats Q-fever Aerosols from birthing by-products, dust, leather, wool, tick bite. Fever, chills, profuse sweating, malaise, anorexia, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, cephalalgia, retroorbital pain, slight cough, mild expectoration, chest pain. Vaccine (Not available in USA). Q-fever titer. TBD Cats Rabies Bite, contact with infected tissue or body fluids. Fever, headache, agitation, confusion, excessive salivation. Avoid contact with wild animal, use appropriate PPE. Rabies vaccine. Known in wild animals, none in Lab animals. Cats Salmonellosis Fecal/Oral, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever. Personal hygiene. No TBD Cats Scabies Close contact. Irritation, pruritis, itching. Wear protective clothing, gloves and high boots of a material that mites cannot penetrate. No TBD Cats Sporothrix schenckii Contact through a cutaneous lesion, inhalation of fungs. Nodule or pustule at point where broken skin allowed inoculation, cough, expectoration, dyspnea, pleuritic pain, hemoptysis, weight loss, fatigue, slight rise in body temperature. Wear protective clothing, use gloves to handle animal with cutaneous lesions. No TBD Cats Toxoplasmosis Ingestion of oocysts from hands, or food or water contaminated with feces of infected animal. Mild fever, persistent lymphadenopathy in one or more lymph nodes, asthenia, cephalalgia, lethargy, facial paralysis, hemiplegia, coma, weakness. Potential birth defects. Personal hygiene, PPE. Use respirator or avoid cleaning litter boxes if pregnant. No Yes fecal material; lab procedures. Cats Visceral larva migrans Ingestion of larva from contaminated hands, or food or water. Eosinophilia, fever, asthenia, digestive symptoms, abdominal pain. Personal hygiene, PPE. No Fecal/oral ingestion. Cats Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Fecal/Oral, contaminated food and water Mesenteric adentis or pseudoappendicitis, acute abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, pyrexia, rashes, nausea. Personal hygiene, PPE. No TBD References:

Fox JG, Cohen BJ, Loew FM, eds. Laboratory Animal Medicine. Academic Press, Orlando, 1984, p 621. Schwabe CW. Veterinary Medicine and Human Health, 3rd edition. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1984, pp 352-362.

Willard MD, et al. Gastrointestinal zoonoses. Small Animal Practice, 1987.

17:152-155. Schwabe CW. Veterinary Medicine and Human Health, 3rd edition. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1984, p 615. Fox JG. Campylobacteriosis - a "new" disease in laboratory animals. Laboratory Animal Science, 1982, 32:615-637.

Rohrbach BW. Tularemia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, Aug 15, 1988, 193:4. Steel JH, ed. CRC Handbook Series in Zoonoses, Section A, Volume II. CRC Press, Bola Raton, Florida, 1980, pp 161-193. Mandell GL, ed. Infectious Diseases, Volume 2. Churchill Livingstone, Inc., 1995, pp 2060-2068.

Bernard KW, et al. Q Fever control measures: recommendations for research facilities using sheep. Infection Control, 1982, 3(6):461-465. Fox JO, Cohen BJ, Loew FM, eds. Laboratory Animal Medicine. Academic Press, Orlando, 1984, pp 622-623. Grant CG, et al. Q Fever and experimental sheep. Infection Control, 1985, 6(3):122-123

Revised 10/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

-

Fish

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Fish

Aside from food poisonings, the overall incidence of transmission of disease-producing agents from fish to humans is low. There are, however, a number of agents that are found in fish and aquarium water that have the potential to be transmitted to humans. In general, humans contract fish borne disease through ingestion of infected fish tissues or aquarium water or by contamination of lacerated or abraded skin. An important feature of many of the disease causing agents is their opportunistic nature. The development of disease in the human host often requires a preexisting state that compromises the immune system. If you have an immune-compromising medical condition or you are taking medications that impair your immune system (steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, or chemotherapy), you are at-risk for contracting a fish borne disease and should consult your physician. The following is a list of known and potential fish borne zoonoses.

Mycobacterium: Organisms in the genus Mycobacterium are non-motile, acid-fast rods. Two species, M. fortuitum and M. marinum, are recognized as pathogens of tropical fish. Humans are typically infected by contamination of lacerated or abraded skin with aquarium water or fish contact. A localized granulomatous nodule (hard bump) may form at the site of infection, most commonly on hands or fingers. The granulomas usually appear approximately 6-8 weeks after exposure to the organism. They initially appear as reddish bumps (papules) that slowly enlarge into purplish nodules. The infection can spread to nearby lymph nodes. More disseminated forms of the disease are likely in immunocompromised individuals. It is possible for these species of mycobacterium to cause some degree of positive reaction to the tuberculin skin test.

Aeromonas spp.: Aeromonad organisms are facultative anaerobic, gram-negative rods. These organisms can produce septicemia (a severe generalized illness) in infected fish. The species most commonly isolated is A. hydrophilia. It is found world wide in tropical fresh water and is considered part of the normal intestinal microflora of healthy fish. Humans infected with Aeromonas may show a variety of clinical signs, but the two most common syndromes are gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting and diarrhea) and localized wound infections. Again, infections are more common and serious in the immunocompromised individual.

Other Bacteria and Protozoa: Below is a list of additional zoonotic organisms that have been documented in fish or aquarium water. Human infections are typically acquired through ingestion of contaminated water (resulting in gastroenteritis symptoms) or from wound contamination.

Gram-negative Organisms: Plesiomonas shigelloides, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Klebsiella spp., Edwardsiella tarda

Gram-positive Organisms: Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Clostridium, Erysipelothrix, Nocardia

Protozoa: CryptosporidiumAllergic Reactions to Fish: Human sensitivity to fish proteins in the laboratory setting is rare. It remains possible, however, to become sensitized to fish proteins through inhalation or skin contact. If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health Director at ehsocchealth@ucr.edu to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risk for Exposure at UCR Fish Aeoromonas (link opens in a new tab) Fecal/oral contact with fish water Gastrointestinal disorder (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) Personal hygiene, PPE No Yes Fish Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Contact with animal and animal products through wounds and skin abrasions Arthritis in the finger joints, burning sensation, pulsating pain, intense pruritus Personal hygiene, PPE, proper treatment of wounds No Yes Fish Salmonellosis (link opens in a new tab) Fecal/Oral, contaminated food and water Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever Personal hygiene No Yes Fish Mycobacterium (link opens in a new tab) Contact with animal and animal products through wounds and skin abrasions The most frequent sign is a slowly developing nodule (raised bump) at the site the bacteria entered the body. Frequently, the nodule is on the hand or upper arm. Later the nodule can become an enlarging sore (an ulcer). Swelling of nearby lymph nodes occurs. PPE, Review Mycobacterium Post-Exposure Plan (PEP) No Yes References:

Louis J. DeTolla, S. Srinivas, Brent R. Whitaker, Christopher Andrews, Bruce Hecker, Andrew S. Kane and Renate Reimschuessel. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Fish in Research ILAR J (1995) 37(4): 159-173 doi:10.1093/ilar.37.4.1 (link opens in a new tab).

Microbial Presence:

Thune, R. L., L. A. Stanley, R. K. Cooper. 1993. Pathogenesis of Gram-negative bacterial infections in warmwater fish (link opens in a new page). Annual Review of Fish Diseases 3:37-68.

Transgenic and Laboratory Fishes:

Hallerman, E. M. and A. R. Kapuscinski. 1995. Incorporating risk assessment and risk management into public policies on genetically modified finfish and shellfish. Aquaculture 137:9-17.

Hashish E, Merwad A, Elgaml S, Amer A, Kamal H, Elsadek A, Marei A, Sitohy M. Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish and man: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management; a review. Vet Q. 2018;38:35–46. doi:10.1080/01652176.2018.1447171 (link opens in a new tab).

Ostrander, G.K. 2000. The Laboratory Fish. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Warmbrodt, R.D. and V. Stone. 1993. Transgenic fish research: a bibliography (link opens in a new tab). National Agriculture Library. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD.

Winn, R. 2001. Transgenic fish as models in environmental toxicology. Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 43:322-329.

Revised 07/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

-

Rabbits

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Rabbits

Rabbits are generally docile animals that are easy to handle and pose minimal risks of contracting a zoonotic disease to laboratory personnel and animal care staff. The development of disease in the human host often requires a preexisting state that has compromised the immune system. If you have an immune-compromising medical condition or you are taking medications that impair your immune system (steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, or chemotherapy), you are at higher risk for contracting a rabbit disease and should consult your physician. The primary concern when working with rabbits is developing allergies and injuries from scratches and bites. Prior to your assignment, you should receive training in specific handling techniques and specific protective clothing requirements. The following is a list of known and potential rabbit zoonoses.

Pasteurella multocida: This bacteria lives in the oral cavity or upper respiratory tract of rabbits. Human infection is generally associated with a rabbit bite or scratch. Human infection is generally local inflammation around the bite or scratch, possibly leading to abscess formation with systemic symptoms.

Cryptosporidiosis: An extracellular protozoal organism, cryptospordium is transmitted via the fecal-oral route; waterborne transmission is also important. In humans, infection varies from no symptoms to mild gastrointestinal symptoms to marked watery diarrhea. The infection is generally self-limited and lasts a few days to about 2 weeks. In immunocompromised individuals, the illness is more severe.

Other Potential Diseases Associated with rabbits: While none of the following are commonly associated with laboratory rabbits, these diseases are associated with rabbits. Brucella suis biotype 2, cheyletiella infestation, francisella tularensis, plague, Q-fever, and trichophyton mentagrophytes.

Allergic Reactions to Rabbits: Allergies to rabbit fur and dander are well documented. A major glycoprotein allergen can occur in the fur of rabbits and minor allergenic components found in rabbit saliva and urine have been identified as sources of allergies. If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health at 951-827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Tell your physician you work with rabbits. Whenever you are ill, even if you're not certain that the illness is work-related, always mention to your physician that you work with rabbits. Many zoonotic diseases have flu-like symptoms and would not normally be suspected. Your physician needs this information to make an accurate diagnosis. Questions regarding personal human health should be answered by your physician.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly. If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to animals and their housing materials. For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation (link opens in a new tab). For treatment locations visit: Medical Treatment Facilities (link opens in a new tab).

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Rabbits Brucella suis biotype 2 Contact with animal and newborn animal, ingestion of animal products, inhalation of airborne agents, contaminated food and water. Fever, chills, profuse sweating, weakness, insomnia, constipation, anorexia, headache, arthralgia, general malaise, irritation, nervousness, depression. Personal hygiene, use of protective clothes, and disinfectants. No TBD Rabbits Cheyletiella infestation Contact with infected animals. Mites causing papular, pruriginous dermatitis on arms, thorax, waist, thighs. PPE, personal hygiene, repellants. No TBD Rabbits Francisella tularensis Ingestion of contaminated water and food, aerosols, scratch, bite, tick. Rising and falling fever, chills, asthenia, joint and muscle pain, cephalalgia, vomiting, ulceroglandular. Wear protective clothing, protection of food and water. No TBD Rabbits Plague Flea bite, skin abrasions or bites. Fever, chills, cephalalgia, nausea, generalized pain, diarrhea, constipation, toxemia, shock, arterial hypotension, rapid pulse, anxiety, staggering gait, slurred speech, mental confusion, prostration. Flea and rodent control, PPE. No TBD Rabbits Q-fever Aerosols, birthing by-products, dust, leather, wool, tick bite. Fever, chills, profuse sweating, malaise, anorexia, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, cephalalgia, retroorbital pain, slight cough, mild expectoration, chest pain. PPE, personal hygiene, Vaccine not available in USA.. Q-fever Titer Yes TBD Rabbits Trichophyton mentagrophytes Contact with skin, spores contained in the hair and dermal scales shed by the animal. Inflammatory dermatophytosis. Avoid contact with wild animal, isolate sick animal and treat with topical antimycotics or griseofulvin administered orally, and remains of hair and scales should be burned and rooms, stables, and all utensils should be disinfected. No TBD References

Acha, PN and B Szyfres. 1989. Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C.

Hillyer, EV and KE Quesenberry. 1997. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. WB Saunders Co., Philadelphia, PA.

Harkness, JE and JE Wagner. 1995. The Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents. Williams & Wilkins, Media, PA.

Manning, PJ, DH Ringler and CE Newcomer. 1994. The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Revised 10/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

-

Reptiles

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Reptiles

Reptiles should always be considered wild animals and handled with a great deal of respect. No one should be handling a reptile unless they have had training on safe handling procedures. Reptiles can use their claws to dig into flesh or clothing, or they can scramble in an attempt to be freed or they will thrash around in an attempt to escape. Moving or handling venomous snakes requires special skills and experience. Reaching or attempting to grab a freed reptile can cause injury to neck, back, and shoulder muscles.

The overall incidence of transmission of disease-producing agents from reptiles to humans is relatively low. In general, humans acquire these diseases through poor personal hygiene. The following are some of the zoonotic diseases that can be acquired by handling reptiles.

Salmonella: This bacterium inhabits the intestinal tract of many animals and humans. Salmonella occurs worldwide and is easily transmitted through ingestion of contaminated material, either directly or indirectly. Common symptoms of the illness are acute gastroenteritis with sudden onset of abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and fever. The use of antibiotic treatment is standard treatment for this illness.

Aeromonas Hydrophila: This is a species of bacterium that is present in all freshwater environments and in brackish water. Infection is acquired through open wounds or by ingestion of contaminated food or water. Common symptoms are those associated with gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and wound infections.

Edwardsiella tarda: This is a gram-negative rod bacteria usually found in the intestines of cold-blooded animals and in fresh water. It is an opportunistic pathogen occasionally causing acute gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and can be associated with meningitis, septicemia, and wound infections. Mode of transmission is via the fecal/oral route or ingestion of contaminated food. Antibiotics are used for treatment.

Melioidosis: Also called Whitmore's disease is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. Melioidosis is clinically and pathologically similar to glanders disease, but the ecology and epidemiology of melioidosis are different from glanders. Melioidosis is predominately a disease of tropical climates, especially in Southeast Asia where it is endemic. The bacteria causing melioidosis are found in contaminated water and soil and are spread to humans and animals through direct contact with the contaminated source. Illness from melioidosis can be categorized as acute or localized infection, acute pulmonary infection, acute bloodstream infection, and chronic suppurative infection. Inapparent infections are also possible. The incubation period (time between exposure and appearance of clinical symptoms) is not clearly defined, but may range from 2 days to many years.

Allergic Reactions to Reptiles: Human sensitivity to reptile proteins in the laboratory setting is rare. It remains possible however, to become sensitized to reptile proteins through inhalation or direct skin contact.

If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health at 951-827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Tell your physician you work with Reptiles. Whenever you are ill, even if you're not certain that the illness is work-related, always mention to your physician that you work with reptiles. Many zoonotic diseases have flu-like symptoms and would not normally be suspected. Your physician needs this information to make an accurate diagnosis. Questions regarding personal human health should be answered by your physician.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly. If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to animals and their housing materials. For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation (link opens in a new tab). For treatment locations visit: Medical Treatment Facilities (link opens in a new tab).

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Reptiles Aeronomonas hydrophila Contamination through wounds or various traumas. Diarrhea, slight fever, abdominal pains, blood and mucus in feces, weight loss, dehydration, cellulitis. Clean and disinfect wounds, personal hygiene, PPE. No TBD Reptiles Campylobacteriosis Fecal, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, visible or occult blood, headache, muscle and joint pain. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Escherichia coli Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, abdominal pains, fever, vomiting, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, azotemia, thrombosis in terminal arterioles and capillaries. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Mycobacterium ulcerans Handling infected animals. Infections start as erythematous nodules on the extremities and gradually become large, indolent ulcers with necrotic base. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Pentastosomiasis Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water. Prostatitis, ocular infection, acute abdomen, lacrimation, nasal discharge, dyspnea, dysphagia, vomiting, headaches, photophobia, exophthalmia. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Salmonellosis Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Sparganosis Contaminated food and water. Pruritus, urticaria. Ocular sparganosis consist of painful edema of eyelids with lacrimation and pruritus. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Reptiles Burkholderia pseudomalle Contaminated soil and surface water and contact with contaminated wounds. Localized skin infection, pulmonary infections and acute blood stream infections. Wearing boots in agricultural situations, Universal precautions in hospitals/care facilities and PPE personal hygiene. No TBD References

Johnson-Delany, CA. 1996. Reptile Zoonoses and Threats to Public Health. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery. DR Mader, ed. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. pp. 20-33.

Acha, PN and B Szyfres. 1989. Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals. 2nd Ed. Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C.

Revised 10/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

-

Rodents (Rat, Mouse, Guinea Pig, Hamster)

Potential Injury and Zoonotic Diseases for Rodents (including rats, mice, hamsters, guinea pigs & gerbils)

Potential Zoonotic Diseases: Colony-born rodents are generally docile, but may occasionally inflict injury such as a bite or scratch. While rodents may carry organisms that may be potentially infectious to humans, the major health risk to individuals working with laboratory rodents is the development of an allergy. The development of disease in the human host often requires a preexisting state that compromises the immune system. If you have an immune-compromising medical condition or you are taking medications that impair your immune system (steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, or chemotherapy) you are at higher risk for contracting a rodent disease and should consult your physician. The following is a list of some of the potential rodent zoonoses.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis: Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) is caused by the arenavirus commonly associated with hamsters, but does infect mice. LCM is rare in laboratory animal facilities, more common in the wild. Transmission to humans is through contact with infected tissues including tumors, feces, urine, or aerosolization of any one of these. Disease in humans is generally flu-like symptoms that range from mild to severe.

Campylobacter: This is a gram negative bacterium that has a worldwide distribution. Although most cases of human campylobacteriosis are of unknown origin, transmission is thought to occur by the fecal-oral route through contamination of food or water, or by direct contact with infected fecal material. The organism has also been isolated from houseflies. Campylobacter is shed in the feces for at least six weeks after infection. Symptoms are acute gastrointestinal illness: diarrhea with or without blood, abdominal pain, and fever. It may cause pseudoappendicitis and, rarely, septicemia and arthritis. Usually it is a brief self-limiting disease that can be treated with antibiotics.

Leptospirosis: Is bacteria found in many animals but are most commonly associated with livestock and dogs. The source of infection can be from any of the following: rats, mice, voles, hedgehogs, gerbils, squirrels, rabbits, hamsters, reptiles, dogs, sheep, goats, horses, and standing water. Leptospires are in the urine of infected animals and are transmitted through direct contact with urine or tissues via skin abrasions or contact with mucous membranes. Transmission can also occur through inhalation of infectious droplet aerosols and by ingestion. The disease in people is a multi-systemic disease with chronic sequelae. An annular rash is often present with flu like symptoms. Cardiac and neurological disorders may follow and arthritis is a common end result.

Hantavirus Infection: Hantavirus occurs mainly among the wild rodent populations in certain portions of the world. Rats and mice have been implicated in outbreaks of the disease. A hantavirus infection from rats has very rarely occurred in laboratory animal facility workers. Rodents shed the virus in their respiratory secretions, saliva, urine and feces. Transmission to humans is via inhalation of infectious aerosols. The form of the disease that has been documented after laboratory animal exposure is characterized by fever, headache, myalgia (muscle aches) and petechiae (rash) and other hemorrhagic symptoms including anemia and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Other Bacterial Diseases: There are several other bacterial diseases that are possibly, though rarely spread through working with laboratory rodents. These include yersinia and tularaemia.

Allergic Reactions to Rodents: By far the greatest occupational risk to working with rodents is allergic reaction or developing allergies. Those workers that have other allergies are at greater risk. Animal or animal products such as dander, hair, scales, fur, saliva and body waste, and urine in particular, contain powerful allergens that can cause both skin disorders and respiratory symptoms. The primary symptoms of an allergic reaction are nasal or eye symptoms, skin disorders, and asthma. If you have symptoms you are strongly advised to contact the Occupational Health at 951-827-5528 to discuss this issue and arrange for follow-up with an occupational health physician.

Tell your physician you work with animals: Whenever you're ill, even if you're not certain that the illness is work related, always mention to your physician that you work with animals. Many zoonotic diseases have flu-like symptoms, and your physician needs this information to make an accurate diagnosis.

Seek Medical Attention Promptly. If you are injured on the job, promptly report the accident to your supervisor even if it seems relatively minor. Minor cuts and abrasions should be immediately cleansed with antibacterial soap and then protected from exposure to animals and their housing materials. For more serious injuries seek medical services through Workers Compensation (link opens in a new tab). For treatment locations visit: Medical Treatment Facilities (link opens in a new tab).

Species Biological Hazard/Pathogen Route of Transmission Clinical Symptoms Prevention/Prophylaxis Medical Surveillance Required Risks for Exposure at UCR Rats & Mice Argentine hemorrhagic fever Skin lesions, ingestion of contaminated products, inhalation of aerosols that come in contact with the conjunctiva and the oral or nasal mucosa. Fever, malaise, chills, fatgue, dizziness, cephalalgia, dorsalgia, conjunctival congestion, retro-orbital pain, epigastralgia, halitosis, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, increased vascularization of the soft palate, axillary and inguinal adenopathy, petechiae on the skin and palate, congestive halo on the gums, epistaxis, gingival hemorrhaging, slowed mental response, unsteady gait, hypotension, bradycardia, muscular hypotonia, osteotendinous hyporeflexia, hemetemesis, melena, muscular tremors in the tongue and hands, confusion or excitability, tonic-clonic convulsive seizures, cerebellar syndrome. Avoid contact with wild animal. Use good personal hygiene and PPE Vaccine available in endemic areas. No TBD Rats & Mice Bolivian hemorrhagic fever Contact with urine, contaminated food and water. Fever, myalgia, conjunctivitis, cephalalgia, cutaneous hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal symptoms, hemorrhaging from gums, nose, stomach, intestines, uterus, hypotension, tremors of tongue, convusions, coma, leukopenia, hemoconcentration, proteinuria, adenopathy, focal hemorrhagees in the gastric and intestinal mucosa, lungs, and brain. Avoid contact with wild animal. Use good personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Endemic typhus Flea bite, contact with conjunctiva, inhalation. Fever, severe cephalalgia, generalized pains, coughing, nervousness, nausea, vomiting, myalgia. Avoid contact with wild animal, good personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Francisella tularensis. Ingestion of contaminated water and food, aerosols, scratch, bite, tick. Rising and falling fever, chills, asthenia, joint and muscle pain, cephalalgia, vomiting, ulceroglandular. Medical care for all bites from field animals. Wear protective clothing, protection of food and water. Vaccine available for lab workers. No TBD Rats & Mice Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Bite, contact with rodent excreta, aerosol. Chills, myalgia, headache, abdominal pain, coughing, rapid development of respiratory insufficiency, hypotension. Use protective face masks and gloves when handling rodents or traps containing rodents or droppings. Personal hygiene, PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome Bite, contact with rodent excreta, aerosol. Fever, chills, generalized discomfort, myalgia, extensive edema of the peritoneum, severe abdominal and lumbar pain, flushing of the face, neck, thorax, congestion of the conjunctiva, palate, pharynx, shock, capillary hemorrhage, elevated blood urea and creatinine levels, hypertension, nausea, vomiting, hemorrhaging. Use protective face masks and gloves when handling rodents or traps containing rodents or droppings. Personal hygiene and PPE No TBD Rats & Mice Lassa fever Aerosols, direct contact with excreta, or skin lesions. Fever, asthenia, muscular pain, cephalalgia, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, edema of face and neck, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, cough, stertor, thoracic pain, ulcerative pharyngitis, albuminuria, low serum albumin, elevated urea nitrogen, capillary hemorrhaging, central nervous system involvement, respiratory insufficiency, oliguria, shock, circulatory collapse. Avoid contact with blood or other body fluids, wear masks, gloves, and protective clothing. Good personal hygiene. Contacts who are most exposed can be given ribavirin on a preventative basis.. No TBD Rats & Mice Leptospirosis Contaminated foods, contact. Meningitis, meningoencephalitis, chills, increased body temperature, cephalalgia, slight dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms. Avoid contact with wild animal, protection of food and water, personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Flea bite, skin abrasions or bites. Fever, chills, cephalalgia, nausea, generalized pain, diarrhea, constipation, toxemia, shock, arterial hypotension, rapid pulse, anxiety, staggering gait, slurred speech, mental confusion, prostration. Flea and rodent control, inactivated vaccine, PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Plague Flea bite, skin abrasions or bites. Fever, chills, cephalalgia, nausea, generalized pain, diarrhea, constipation, toxemia, shock, arterial hypotension, rapid pulse, anxiety, staggering gait, slurred speech, mental confusion, prostration. Flea and rodent control, inactivated vaccine, PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Rabies Bite, contact with infected tissue or body fluids. Fever, headache, agitation, confusion, excessive salivation. Avoid contact with wild animal, use appropriate PPE. Medical care for all wild animal bites. No TBD Rats & Mice Rickettsialpox Mouse bite, mite bite. Chills, profuse sweating, intermittent fever, cephalalgia, myalgia, nasal discharge, cough, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain. Avoid contact with wild animal, incinerate trash. Medical care for all wild animal bites. No TBD Rats & Mice Salmonellosis Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water. Diarrhea, vomiting, low grade fever. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Spirillium minus Bite, rat saliva. Fever, headache, chills, myalgia, arthralgia, endocarditis, pneumonia, metastatic abscesses, anemia, vomiting, pharyngitis. Avoid contact with wild animal, protection of food and water. Medical care for all animal bites. No TBD Rats & Mice Trichophyton mentagrophytes Contact with skin, spores contained in the hair and dermal scales shed by the animal. Inflammatory dermatophytosis Avoid contact with wild animal, isolate sick animal and treat with topical antimycotics or griseofulvin administered orally, and remains of hair and scales should be burned and rooms, stables, and all utensils should be disinfected. No TBD Rats & Mice Venezuelan Hemorrhagic Fever Contact with infected rodent and their excreta. Fever, prostration, cephalalgia, arthralgia, cough, pharyngitis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, epistaxis, bleeding gums, menorrhagia, melena, conjunctivitis, cervical adenopaathy, facial edema, pulmonary crepitation, petechiae, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia. Avoid contact with wild animal, personal hygiene, PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Yersinia enterocolitica Fecal/oral, contaminated food and water. Fever, hypotension, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, sore throat, bloody stool, cutaneous eruptions, joint pain. Personal hygiene and PPE. No TBD Rats & Mice Allergy: Saliva, Urine, Blood, Dander or Fur Contact with skin or inhalation Respiratory irritant, Asthma, Dermatitis. Respiratory protection, gloves. Possible TBD References:

The management of work-related asthma guidelines: a broader perspective Eur Respir Rev (2012) 21(124): 125-139

Occupational Asthma Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. (2005) 172(3): 280-305

Prevention of laboratory animal allergy - Occupational Medicine

Revised 10/2025. Information taken from UC Davis.

Post Exposure Plans

-

Botulism

The Exposure Response Plan for Laboratory Handling of Botulinum Toxin Type A provides comprehensive guidance for the safe handling, containment, and emergency response procedures associated with the use of Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT/A) in research and laboratory settings. This plan outlines potential exposure routes, clinical symptoms, immediate response actions, and medical management, including coordination with public health authorities for antitoxin access. It also defines reporting requirements, personal protective equipment standards, and decontamination protocols to ensure compliance with institutional biosafety policies and federal regulations.

Exposure Response Plan for Laboratory Handling of Botulinum Toxin Type A (link opens in a new tab)

-

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

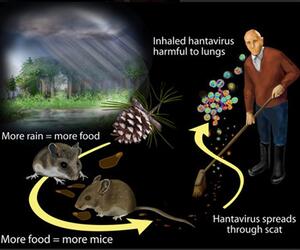

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) is a respiratory disease caused by a virus known as Sin Nombre Virus.

The virus is carried by wild rodents, especially deer mice. The virus produces no clinical signs in the deer mice, but can produce a deadly infection in man - over 50% of human cases have been fatal.

What is Hantavirus?

Hantavirus is a serious and potentially fatal illness transmitted by infected rodents. Humans can become infected through:

- Inhaling dust contaminated with rodent urine, droppings, or saliva

- Direct contact with rodent bodily fluids

- (Rarely) through rodent bites

While dogs and cats are not direct carriers, they may inadvertently expose humans to infected rodents.

Primary Carrier in California:

Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus)

- Size: Comparable to a house mouse

- Color: Pale gray to reddish-brown with a white belly and feet

- Tail: Bi-colored and slightly shorter than the body

- Habitat: Found in forests, grasslands, chaparral, and brushy areas throughout California

Who’s at Risk at UCR?

- Field researchers or students handling or trapping wild rodents

- Staff cleaning field stations, barns, attics, or storage areas

- Maintenance personnel working in crawl spaces or unused buildings

- Campers or students working in remote or rural field locations

Recognizing Hantavirus Symptoms

Symptoms typically appear 1–6 weeks after exposure and may include:

- High fever (101–104°F)

- Muscle aches, chills, and headache

- Abdominal, joint, or back pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Difficulty breathing due to fluid in the lungs

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) can be fatal. If symptoms develop after potential exposure, seek immediate medical care and inform your provider of the rodent exposure.

Prevention Measures

Rodent Elimination

- Use snap traps baited with peanut butter for at least one week

- Treat affected areas for fleas as needed

- Use tamper-resistant bait stations in accordance with UC policy

Disposal Protocol

- Spray rodents and contaminated materials with disinfectant before handling

- Use gloves or an inverted plastic bag to handle carcasses

- Seal waste in a plastic bag and dispose of in a rodent proof container

Safe Cleaning Practices

Before entering a rodent infested area:

- Air out the area for at least 30 minutes

- Wear gloves, eye protection, N95 or P100 mask, and protective clothing

For Cleaning

- Use a bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) or an EPA registered disinfectant

- Spray all contaminated materials before and after handling — do not sweep or vacuum

- Mop floors, disinfect hard surfaces, and wash bedding/clothing in hot water

UCR Fieldwork Safety Guidelines

- Attend EH&S Field Safety & Hantavirus Awareness Training

- Wear HEPA-filtered respirators in enclosed or high-risk rodent areas (contact EH&S medical clearance and for fitting)

- Decontaminate reusable PPE and equipment after field use

- Do not eat, drink, or touch your face when handling rodents or cleaning traps

Working with Laboratory and Wild Rodents

- Lab colonies of deer mice must test negative for hantavirus and be re-tested regularly (check with your facility veterinarian)

- Do not mix wild-caught mice with lab-reared colonies

- Isolate wild-caught rodents until cleared by testing

- Field biologists must treat wild deer mice as potentially infected and wear EH&S-approved HEPA respirators when handling or cleaning

When cleaning rodent-infested structures

- Wear a fitted HEPA respirator and gloves

- Ventilate the structure for at least 24 hours

- Thoroughly spray all surfaces with disinfectant

- Disinfect gloves before removal and wash hands afterward

- Avoid sleeping in contaminated areas

Need Help or More Information?

Contact Occupational Health:

📧 ehsocchealth@ucr.edu

📞 (951) 827-9902

🌐 ehs.ucr.edu/occupational-health (link opens in a new tab)Resource: Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome - CDPH (link opens in a new tab)

PDF version:

Hantavirus Awareness & Prevention Guide (link opens in a new tab)

-

Herpesvirus

Viruses and viral vectors have become a staple of the molecular biology community. As such, it is important for users to understand the origins of these tools and potential implications of their use. Read "Working with Viral Vectors: Herpesvirus" to learn more on virology, clinical features, epidemiology, treatment, laboratory hazards, Personnel Protective Equipment (PPE), disinfection, instructions in the event of an exposure, and use with animals.

Working with Viral Vectors: Herpesvirus (link opens in a new tab)

-

Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviral vectors are based on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) which is the virus responsible for the development of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Lentiviruses are a subclass of retroviruses which can infect both proliferating and non-proliferating cells. Lentiviral vectors have been modified to provide a safer version of the HIV virus in which the viral replication genes have been removed. During infection, there is a possibility that the lentivirus may convert to a replication competent state. Although this scenario is highly unlikely, monitoring for such a possibility is encouraged, since such a conversion could compromise laboratory safety.

Read "Working with Lentiviral Vectors and Post Exposure Plan (PEP)" to learn more on the modes of transmission, laboratory hazards, signs and symptoms, prophylaxis, PPE, decontamination, special handling procedures, and reporting exposure incidents.

Working with Lentiviral Vectors and Post Exposure Plan (PEP) (link opens in a new tab)

-

Listeria monocytogenes